The Mount Lyell Disaster of 1912

On the 12th of October 1912, a fire broke out in North Mount Lyell mine. One hundred and seventy men entered the mine that day. Forty-two were to die there.

The fire started on Saturday morning between 11:15am and 11:30 am, when the pump house on the 700ft level of the mine was reported as being on fire. The fire had originated in a pump motor at the 700ft level, igniting the chamber house. This was lined with King Billy pine, a very inflammable wood, and with oily waste about the fire probably took hold within a few minutes.

The fire was first discovered by Thomas Burns who was in charge of two pump motors, one at the 700ft level, and one at the 1,100ft level. He was at the 1,100 ft level for a short while, and on returning to the 700ft level and finding smoke that was almost overpowering he immediately went up the shaft to give the alarm. In a very short time smoke had filled the shaft above and below the 700ft, making it impossible to see and very difficult to breathe.

Some managed to get to the cage and were taken up to the surface. Seventy-three men made their way to safety on the first day, but there was confusion as to the status of the fire and the numbers of casualties and survivors. Many men became trapped because they were working in remote sections of the mine and didn’t know of the fire until it was far too late, as there was no automated emergency warning system. Instead, men had to run along the levels calling to the miners to tell them of the danger.

The rescue attempt involved the transportation of breathing equipment from a Victoria mining town to Queenstown via Bass Strait and railway. The SS Loongana brought the rescue equipment across Bass Strait. She made the crossing in thirteen hours thirty-five minutes, a record which stood for many years, and the train times between Burnie and Queenstown were never exceeded.

It had been suggested that a diving suit might help rescue operations and one was found in Burnie and rushed to the site. Someone was found to wear it into the mine and he descended to the 850ft level. He was brought up again, however, as the suit was found to be unsuccessful for work in the confines of the mine as its weight was too great and it was not possible to bend while wearing it.

Meanwhile, the change house had been turned into a makeshift hospital. About a dozen beds were moved into it, and a large stock of blankets brought in. The building was heated and medical supplies were in readiness for any miners who were rescued.

During the rescue party’s attempts to find any men alive, they came across the bodies of a group of men on the 700 ft level. One of these, Joe McCarthy, had pinned a note to a timber with a ‘spider,’ a tool used by miners. The note read:

Seven hundred level. North Lyell mine, 12-10-12.

If anyone should find this note convey to my wife.

Dear Agnes. I will say good-bye. Sure I will not see you again any more.

I am pleased to have made a little provision for you and poor little Lorna.

Be good to our little darling.

My mate, Len Burke, is done, and poor old V. and Driver too.

Good-bye, with love to all.

Your loving husband, Joe McCarthy

One of the rescued miners, Richard O’Conner, told his story to the local paper. He described working at the 850ft level and at 12 o’clock hearing shouts that there was a fire in the mine. For some reason he thought this might be a joke, until Albert Gadd appeared, organising the men to get to the cage and up to the surface. The smoke was getting so thick they couldn’t see, and were becoming weak. O’Conner described going up in the cage as terrible, as the miners were stifled by smoke and becoming weaker all the time, and they had to hold each other up. After being revived by the fresh air on the surface they gave assistance where they could.

The Albert Gadd mentioned by O’Conner was one of the miners who escaped death that day and re-entered the mine again and again to assist in the rescue efforts. Local papers reported that Gadd carried out heroic rescue work at the mine for several days after the disaster, during which he inhaled quantities of carbon monoxide gas fumes. He was hospitalised in Launceston and died on 20th February 1913 from carbon monoxide poisoning. Gadd’s wife gave birth to a son two months after his death. Gadd was posthumously awarded the Clarke Gold Medal by the Royal Humane Society in Melbourne.

There were many other stories of heroism from the rescue. The underground foreman, Mr Cox, sent up four or five cages of men. Almost insensible by that time, Cox was put into the next cage and sent to the surface, where he was discovered to be so sick that he was taken to hospital. Mr Sawyer, the New South Wales Inspector, was brought out of the mine in a state of collapse. He had previously been seen descending with the cage almost each time it went down. A little after 9am on Sunday morning the cage was sent down and one man, Bert Parnham, was brought to the surface. Before fainting Parnham told them that there were three others on the next level. The cage was sent down and returned with the other three men, who were in good condition. Parnham had been calling for about an hour to the men on the next level in order to keep their spirits up. The three men reported they had used compressed air to keep the smoke away from them. They had also crawled to the shaft a couple of times but had to return to their position of comparative safety as the smoke was too thick.

By Saturday night local papers reported that Queenstown had come to a standstill. There was conflicting news coming from the mine – that the smoke from the mine had become less, and in the next moment that it had increased and flame was reaching from the shaft high into the air– and everyone was hoping for answers. People were gathered in groups in the streets, with a bigger crowd gathered near the railway station where any Queenstown men rescued from the mine would be brought.

Sunday morning saw wet weather, which seemed in keeping with the despondent feeling of the people who gathered at the mine, among them women who had husbands, brothers, and other loved ones underground, and who wanted to be first to hear any news. There were around one hundred women at the tunnel mouth, many of whom had remained all night at the mine, some of them with children. Large coal fires had been made and were kept burning all night. People kept arriving from Queenstown, Linda Valley, and Gormanston all morning, standing in the rain staring at the tunnel mouth and at the thin smoke which emerged from the shaft. The smoke was less dense than previously, now resembling steam, and hopes ran high that the men had a chance of being rescued alive, but as the hours passed anxiety continued to grow.

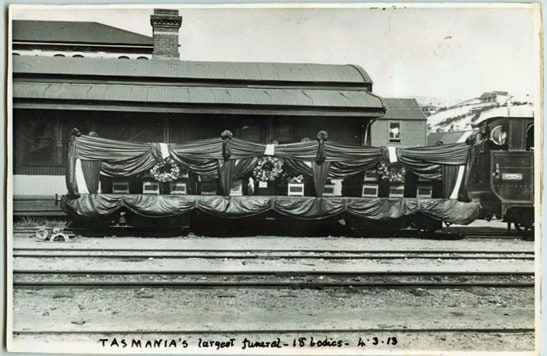

The final tally was forty-two lives lost, and the bodies were buried in unmarked graves in the Queenstown General cemetery. The first two bodies recovered had been buried in the Linda Cemetery, however when the final body to be recovered was buried, the first two bodies were moved from Linda and also buried in the Queenstown general cemetery.

A Royal Commission was held and an open verdict was brought down. Writing forty years after the disaster, Geoffrey Blainey covers the details of the disaster in The Peaks of Lyell. Peter Schulze’s book An Engineer Speaks of Lyell, which was published for the centenary of the event, suggested the most likely cause of the fire was an electrical fault caused by the faulty installation of a pump motor at the 700ft level. Schulze, who had an electrical engineering background and mining experience, concluded that the Royal Commission was manipulated to give a result that best suited the Company, for whom an unfavourable finding could have been financially disastrous.

References:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Lyell_Mining_and_Railway_Company

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1912_North_Mount_Lyell_disaster

Zeehan and Dundas Herald, Monday 14 October 1912

The Examiner, Saturday 22 February 1913

The Mercury, Friday 6 June 1913